NAC Statement on Fibrinogen Concentrate Use in Acquired Hypofibrinogenemia

Andrew Shih, MD

Susan Nahirniak, MD

Taher Rad, MD

Katerina Pavenski, MD

Pouya Pour (BC)

List of abbreviations

Fibrinogen Concentrate

Frozen Plasma

National Advisory Committee on Blood and Blood Products

Solvent-Detergent Plasma

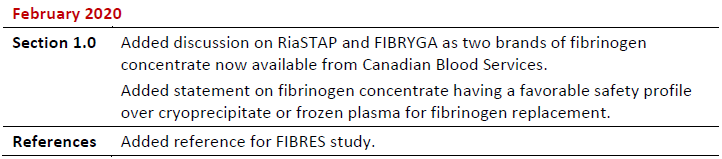

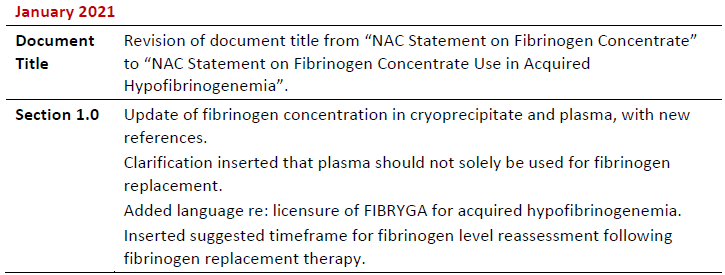

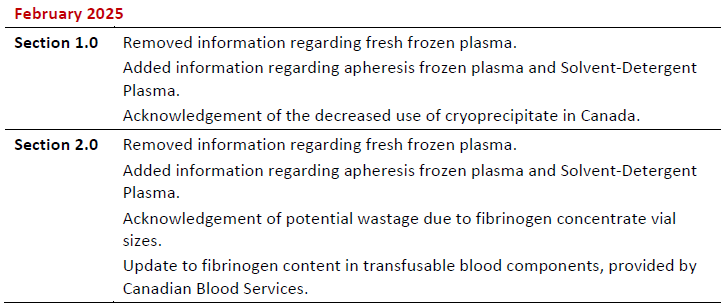

Summary of Revisions

Revision Date

Details

Fibrinogen replacement in the setting of acquired hypofibrinogenemia plays an important role in management of massive bleeding post cardiac surgery, trauma and obstetrical hemorrhage among others. However, there continues to be a lack of evidence firmly guiding fibrinogen replacement product choice as well as ongoing uncertainties as to the optimal target and dose. Fibrinogen concentrate (FC), plasma (including frozen plasma (FP), apheresis frozen plasma (AFP), and Solvent-Detergent Plasma (S/D Plasma)), and cryoprecipitate are currently used to treat acquired hypofibrinogenemia.

There are two FC products currently available in Canada: RiaSTAP (CSL Behring) and FIBRYGA (Octapharma).1,2 Both are licensed for treatment of acute bleeding episodes and perioperative prophylaxis in adult and pediatric patients with congenital afibrinogenemia and hypofibrinogenemia. FIBRYGA is also licensed as a complementary therapy during the management of uncontrolled severe bleeding in patients with acquired fibrinogen deficiency during surgical interventions.2 The use of FCs in acquired hypofibrinogenemia is supported by studies, including a high‐quality randomized trial in bleeding patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery.3

According to data provided by the manufacturers, in addition to fibrinogen, FCs contain trace amounts of the other substances, such as Factor XIII and fibronectin. These substances are not listed as active ingredients in the product monograph and the concentrations in the final product may vary. As such, their clinical relevance, if any, is unknown. Furthermore, both FCs appear to have similar efficacy in improving clot firmness in a dilutional hypofibrinogenemia model in vitro.4

The major difference between these products is related to the product storage: FIBRYGA is stored at room temperature for up to 36 months whereas RiaSTAP is stored in a refrigerator for up to 60 months.1,2

Plasma is indicated for replacement of multiple clotting factor deficiencies and should not be used solely for fibrinogen replacement. The plasma components available are considered equivalent in terms of clinical effectiveness. The additional risks of plasma transfusion include transfusion associated circulatory overload, transfusion related acute lung injury and allergic reactions.

Cryoprecipitate is prepared from slowly thawed FP and is indicated for replacement of fibrinogen in patients with congenital and acquired fibrinogen deficiency (quantitative or qualitative) in the setting of bleeding or an increased risk of bleeding (ex. impending major surgery).

Currently, there is no evidence of superiority of one fibrinogen replacement source over the others in terms of clinical effectiveness for the management of acquired hypofibrinogenemia. FC is pathogen inactivated and has a preferred safety profile in terms of transmissible disease risk as compared to FP and cryoprecipitate. The use of cryoprecipitate has fallen in the past decade from 2.3 per 1000 to 0.1 per 1000 population nationally exclusive of Québec.

Fibrinogen content of the above‐mentioned products is as follows:1,2,5-8

- FC = 0.9-1.3 g per vial

- AFP (thawed): 3.100 +/- 0.647 g/L

- FP (thawed): 2.97 +/- 0.69 g/L

- S/D Plasma (thawed): 2.5 +/- 0.1 g/L

- Cryoprecipitate: 0.366 +/‐ 0.115 g per unit

Optimal dosing of the above‐mentioned products is affected by:

- The inter‐donor variability of fibrinogen content in blood components; and,

- Each unique patient clinical situation, including size, amount and rate of bleeding, baseline fibrinogen level, liver synthetic function and underlying diagnosis.

In a bleeding obstetrical patient with acquired hypofibrinogenemia, fibrinogen replacement is indicated when fibrinogen level is less than 2.0 g/L.9,10 In a massively bleeding or preoperative patient with acquired hypofibrinogenemia, fibrinogen should be replaced when the level is less than 1.5 g/L.11-13

Options for fibrinogen replacement in adult patients with acquired hypofibrinogenemia include the following:1,2,5-8

- FC: 2‐4 g

- FP or AFP: 3-4 units (10‐15 mL/kg)

- S/D Plasma: 4-5 units (10-15 mL/kg)

- Cryoprecipitate: 10 units (1 unit/10 kg)

In neonates and pediatric patients, it is recommended to consult with the product monograph and a specialist with expertise in managing pediatric/neonatal coagulopathy prior to administration of FCs. In published studies of acquired hypofibrinogenemia in neonatal or pediatric populations, FC dosing has ranged between 30‐60 mg/kg.14,15 The smallest FC vial size available is 1 gram. In patients requiring doses smaller than 1 gram, wastage should not be a barrier to FC use in neonatal and pediatric patients.

Following administration of a fibrinogen replacement therapy, repeat bloodwork should be completed within 60 minutes to assess the degree of fibrinogen increment. The expected increment is approximately 0.5‐1.0 g/L.3,7,15

References

- RiaSTAP® Fibrinogen Concentrate (Human) Product Monograph, Control Number: 237751 [Internet]. CSL Behring. 27 May 2020. [cited 2021 01 05]. Available from: https://labeling.cslbehring.ca/PM/CA/Riastap/EN/RiaSTAP-Product-Monograph.pdf

- FIBRYGA® Fibrinogen Concentrate (Human) Product Monograph, Control Number: 230407 [Internet]. Octapharma. 7 June 2017 [updated 2020 11 19; cited 2025 01 25]. Available from: https://pdf.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00058970.PDF

- Callum J, Farkouh ME, Scales DC, et al. Effect of Fibrinogen Concentrate vs Cryoprecipitate on Blood Component Transfusion After Cardiac Surgery: The FIBRES Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019 Oct;322(20):1966–1976. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.17312

- Haas T, Cushing MM, Asmis LM. Comparison of the efficacy of two human fibrinogen concentrates to treat dilutional coagulopathy in vitro. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2018 May;78(3):230‐235. doi: 10.1080/00365513.2018.1437645

- Sheffield WP, Bhakta V, Yi QL, et al. Stability of thawed apheresis fresh‐frozen plasma stored up to 120 hours at 1C to 6C. J Blood Transfus. 2016 Nov;6260792. doi: 10.1155/2016/6260792.

- Sheffield WP, Bhakta V, Talbot K, et al. Quality of frozen transfusable plasma prepared from whole blood donations in Canada: An update. Transfus Apher Sci. 2013 Dec;49(3):440‐446. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2013.06.012.

- Plasma Components. Circular of Information for the Use of Human Blood Components. [Internet] Ottawa: Canadian Blood Services; March 2023. [cited 2025 01 28]. Available from: https://www.blood.ca/sites/default/files/IM-00004_Revision_2.pdf.

- OCTAPLASMA™ Solvent Detergent (S/D) Treated Human Plasma, Submission Control Number: 267497 [Internet]. Octapharma. 11 August 2005 [updated 2022 10 31; cited 2025 02 11]. Available from: https://www.octaplasma.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/octaplasma_pm_en_31_oct_2022.pdf

- Collins RE, Collins PW. Haemostatic management of obstetric haemorrhage. Anaesthesia. 2015 Jan;70 Suppl 1:78‐86, e27-8. doi: 10.1111/anae.12913.

- Lier H, von Heymann C, Korte W, et al. Peripartum Haemorrhage: Haemostatic Aspects of the New German PPH Guideline. Transfus Med Hemother. 2018 Apr;45(2):127‐135. doi: 10.1159/000478106.

- Wada H, Thachil J, Di Nisio M, et al. Guidance for diagnosis and treatment of DIC from harmonization of the recommendations from three guidelines. J Thromb Haemost. 2013 Feb;11:761‐7. doi: 10.1111/jth.12155.

- Levy JH, Welsby I, Goodnough LT. Fibrinogen as a therapeutic target for bleeding: a review of critical levels and replacement therapy. Transfusion. 2014 May;54(5):1389‐405. doi: 10.1111/trf.12431.

- Levy JH, Goodnough LT. How I use fibrinogen replacement therapy in acquired bleeding. Blood. 2015 Feb 26;125(9):1387‐93. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-08-552000

- Haas T, Fries D, Velik‐Salchner C, Oswald E, Innerhofer P. Fibrinogen in craniosynostosis surgery. Anesth Analg. 2008 Mar;106(3):725‐731. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318163fb26.

- Galas FRBG, de Almeida JP, Fukushima JT, et al. Hemostatic effects of fibrinogen concentrate compared with cryoprecipitate in children after cardiac surgery: A randomized pilot trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014 Oct;148(4):1647‐55. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.04.029.